Like many well-meaning, left-leaning, oat-milk-drinking adults, my partner and I watched Netflix’s Adolescence with the fascinated dread of watching a gender implode in real time. 1Netflix, Adolescence, 2025. The insecure man, afraid of losing his crown, therefore doubles down on his dominant behaviour. At the heart of it lies a belief that if someone else gains power, the insecure man has lost a Pokémon battle. That fairness is theft. That women, queer people, and basically anyone not currently recording a podcast called The Real Truth About Truth are coming for their turf. But this zero-sum game is a lie. And like all good lies, it wears mirrored sunglasses and sells protein powder on Instagram.

This essay contends that the current wave of reactionary machismo is less a show of strength and more a planetary man-tantrum. And there’s still hope. Hope that men might come to see that lifting others up doesn’t mean getting bench-pressed into oblivion. That empathy is not emasculating. That maybe, just maybe, sharing the world doesn’t mean losing it.

Table of contents:

Introduction

A Rising Tide of Reaction

Contemporary societies are witnessing a surge of reactionary movements: from misogynistic ‘manosphere’ and incel subcultures to anti-woke culture wars, strongman leaders and what has been dubbed a global ‘broligarchy’ of swaggering dealmakers. These phenomena, at first glance disparate, share deep roots. A central thread is patriarchal insecurity: an anxiety among those long privileged by male‐dominated hierarchies, now reacting against perceived loss of status. This insecurity often manifests in a zero-sum worldview, where any gain by women, LGBTQ+ people, or racial and religious minorities is considered a direct loss to the dominant (typically straight male) group. Compounding the issue, digital radicalisation accelerates and amplifies these anxieties – niche resentments that once festered in private now explode across global social media networks, finding community and validation online.

Once upon a time, men were quietly afraid that someone might find their poetry journal. Now, they fear equality will revoke their Wi-Fi. Enter the broligarchy: a term that sounds like a frat invented a government and decided it needed six presidents, all named Chad.

From podcast studios in undisclosed basements to presidential palaces with weird shirtless horse photos, patriarchal panic has gone both mainstream and extremely meme-stream. The fragile ego of the dominant group has found a megaphone in digital spaces where emotional repression is a virtue and “wokeness” is a sorcerer’s curse. And in this algorithm-fuelled hero’s journey, the enemy is not injustice, it’s visibility.

Fear and Loathing in the Manosphere

These forces feed each other in a toxic feedback loop. Economic and cultural shifts (from globalisation to #MeToo to increased diversity in public life) have been cast by reactionaries as a “wounding” of the once-dominant male identity. In far-right memes and messaging, societal decline is portrayed as metonymically embodied in the “wounded masculinities” of the majority male. 2Oxfam America, Masculinities and the Far-Right: Implications for Oxfam’s Work on Gender Justice, 30 October 2019.

Ah yes, the sacred wound. A feeling of loss so profound it has turned the internet into a 24/7 group therapy session with no therapist, no boundaries, and everyone trying to out-grunt each other. Where once society offered rites of passage like “learning to listen” or “sharing your emotions without blaming women,” now it offers Discord servers with names like “TruthHammer420” and YouTube thumbnails featuring red arrows and veins.

This isn’t masculinity in crisis. This is masculinity in a click funnel.

🇧🇷 Fuelled by such grievance, a politics of backlash has emerged. Leaders like Jair Bolsonaro rail against “gender ideology” in defence of God, family, and nation. 3Mark Gevisser, Duda’s victory in Poland helps draw a ‘pink line’ through Europe, 17 July 2020. This is a man whose version of God looks like he bench-presses commandments and does pull-ups off the Ark. Bolsonaro: prophet of pecs, disciple of deeply performative masculinity, defender of family as long as that family includes only men named Rodrigo and at least one aggressive motorcycle. Backlash here isn’t just political, it’s theatrical. It’s a flex in the face of complexity. It’s the refusal to believe that “gender” is not, in fact, a boss level to defeat with raw aggression and a firm handshake.

🇷🇺 Meanwhile Vladimir Putin casts the liberal West as corrupting “traditional values” and even “satanism”. 4Pjotr Sauer, Russia passes law banning ‘LGBT propaganda’ among adults, The Guardian, 24 November 2022. Somewhere, Satan is confused to find himself in a legislative agenda. Putin has taken the global patriarchy’s internal monologue and externalised it with the fervour of a dad who found his son’s eyeliner. For him, queer joy and gender fluidity aren’t cultural shifts, they’re exorcisms-in-progress. If your masculinity is strong, why does it require such fragile laws to protect it?

Online, aggrieved young men congregate in misogynistic forums blaming feminism for their personal frustrations, egging one another on with memes and manifestos. In each case, the patriarchy’s old guard—or those who identify with it—lashes out to reassert a lost sense of dominance.

Let’s be clear: these aren’t casual forums. These are digital locker rooms, filled with the scent of moral panic and expired Axe body spray. Men arrive looking for belonging and leave with a subscription to discontent, radicalised by pixelated masculinity and ironic memes that stopped being ironic eight black-pilled YouTubers ago.

The reaction isn’t a surprise. It’s a strategy. When men feel their dominance slip, they don’t drop the rope, they add spikes. They lash out not because they’re strong, but because they’ve confused volume for virtue. Welcome to backlash-as-identity.

When Losing Power Feels Like Personal Betrayal

This is the great patriarchal paradox: the belief that equality is subtraction. That every right granted to someone else is one pair of aviator sunglasses snatched from the sacred cargo pants of manhood. That if a woman becomes CEO, a man somewhere must lose his barbecue tongs. But here’s the thing: rights aren’t a pizza. If you get a slice, I don’t automatically have to eat the box. And yet, that zero-sum worldview metastasises. It is the logic of the insecure gym mirror, the forum thread turned cult manifesto, the Reddit post that somehow ends in someone declaring war on pronouns.

This essay dives headfirst into that sweaty whirlpool. From the historical foundations of patriarchy to its latest avatars in the manosphere and strongman politics, we will ask the tough questions: What do you do when power won’t love you back? What happens when grievance becomes a lifestyle brand? And would it be possible to bench press your way out of epistemological despair?

Spoiler: no. But let’s explore anyway.

Patriarchy & Machismo: Historical & Philosophical Foundations

The Architecture of Patriarchy

To grasp the current reactionary moment, we must first understand the foundations of patriarchy and machismo. Patriarchy refers to an enduring social system in which men hold primary power and dominate in roles of political leadership, moral authority, and control of property. For much of human history, this system was so taken for granted as “natural” that it remained invisible and unnamed. Fathers ruled families; men ruled states. The concept of patriarchy only entered widespread feminist discourse in the 20th century, as scholars sought to name the invisible mechanism connecting disparate inequalities. The African American feminist bell hooks (a.k.a. Gloria Jean Watkins) simply defines patriarchy as “institutionalised sexism” – a system that insists on male dominance and female subordination. 5bell hooks, Understanding Patriarchy, 2004. Importantly, hooks notes patriarchy is not a conspiracy of all men against all women, but a cultural script enforced by both sexes and harmful to everyone. “To indoctrinate boys into the rules of patriarchy, we force them to feel pain and to deny their feelings,” hooks observes. In other words, patriarchy demands that men amputate emotional parts of themselves to fit a narrow role. This internalised trauma can later manifest as rage or disdain toward those who challenge that role.

Machismo: Dominance as Identity Performance

If patriarchy is the system, machismo is one of its most flamboyant cultural expressions. Originating in Latin American contexts, machismo valorises an “exaggerated masculinity” marked by virility, toughness, and dominance. The machismo code expects men to be self-reliant providers and protectors, while scorning any sign of vulnerability as weakness. Traditionally, the macho was the familial patriarch writ large – authoritative, aggressive, proudly virile. Machismo norms have been documented worldwide (even if the term is Spanish): from the samurai ethic of feudal Japan, to the Victorian ideal of the British gentleman (firm and unemotional). In all cases, a man’s worth is tied to power over others and the suppression of “feminine” traits like empathy or emotional openness. As Simone de Beauvoir famously remarked:

No one is more arrogant toward women, more aggressive or scornful, than the man who is anxious about his virility.

Simone de Beauvoir

That single line – penned in The Second Sex (1949) – uncannily predicts today’s militant masculinity defenders. The more insecure a man is in his masculine identity, the more he overreacts against women or anyone who makes him feel lesser. Patriarchal insecurity, in short, breeds machismo and misogyny as a compensatory creed.

Ressentiment and Misogyny

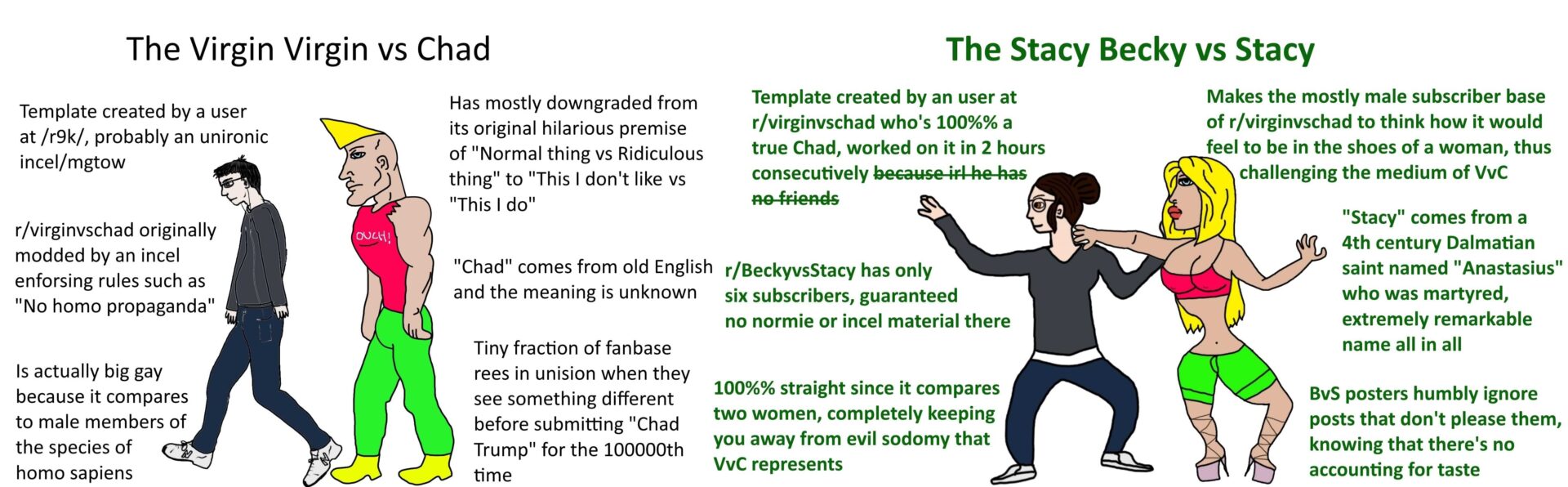

Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche offered a framework for this process through his concept of ‘ressentiment’ (resentment-driven morality). Nietzsche suggested that those who feel weak or thwarted often develop a festering inner resentment that they eventually invert into a moral worldview – proclaiming their “enemy” (the powerful Other) to be evil, and themselves (the supposedly powerless) to be good/virtuous in their victimhood. Recent scholarship connects this ressentiment to the mindset of modern misogynist movements. Studies of incels find that enduring feelings of inadequacy (social, sexual, economic) transmute into contempt and hatred toward those deemed responsible (women, “Chads,” society at large). 6Friedrich Nietz, On the Genealogy of Morality, 1887. The powerless man, unable to attain what he’s been told is rightfully his, reimagines himself as a morally superior victim and strikes back at the “injustices” done to him. Nietzsche saw this pattern in religious and slave moralities, but it maps eerily well onto internet forums of angry young men. Their nihilistic memes about wanting to “destroy Stacy and Chad” are a dark echo of Nietzschean ressentiment, albeit stripped of any philosophical subtlety and channelled into misogyny and racism.

Gender as Performance, Not Destiny

Feminist theorists have further critiqued how patriarchal ideology sustains itself. Judith Butler argued that gender is ultimately a performance: a set of repeated behaviours and norms that create the illusion of an innate male or female ‘essence.’ In Butler’s view, patriarchy’s notion of an eternal gender order is a cultural construct, not a natural law. She warned against treating ‘men’ and ‘women’ as monolithic categories, noting that “not all men are men” in the sense of embodying the macho stereotype. 7Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, 1990. Many men (gay men, gentle men, men of marginalised races or classes) do not fit the patriarchal ideal and thus are policed or punished by it. This insight is crucial: the reactionary cries to “make men men again” are chasing a fantasy of universal masculine power that never truly existed – and in enforcing it, they harm not only women but also men who fall outside the narrow norm.

Insecurity in Power: A Fragile Order

In summary, patriarchy has been the long-standing operating system of social power, and machismo its custom interface – flashy, imposing, but fundamentally about male dominance. Challenges to that order, whether through feminist movements, LGBTQ+ visibility, or minority rights, trigger what Nietzsche would recognise as ressentiment in those who feel dethroned. The insecure patriarch, afraid of losing his crown, doubles down on domineering behaviours. History shows this pattern repeatedly. Today it resurfaces in new guises, fortified by the instant connectivity of the internet. To understand incels posting on Reddit or populist politicians fulminating about ‘wokeism,’ we must keep in mind this baseline: patriarchal masculinity is a brittle construction, one that reacts defensively – often violently – when its authority is questioned. Machismo, misogyny, and authoritarian posturing are age-old coping mechanisms for that insecurity.

Manosphere, Incel Culture & Digital Radicalisation

A Digital Brotherhood of Grievance

One of the clearest manifestations of patriarchal insecurity today is the online ecosystem known as the manosphere: this is an umbrella term for a network of websites, blogs, forums, and communities united by their hostility to feminism and women’s equality. 8Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD), The ‘Manosphere’, 20 September 2022. The manosphere runs the gamut from relatively tame men’s rights discussion groups to openly toxic arenas of incels (“involuntary celibates”), pick-up artists (PUAs), MGTOW (Men Going Their Own Way), “redpill” forums, and so on. What ties these groups together is a shared narrative that men (especially straight men) are the real victims of modern society – emasculated by feminism, ignored by society, deprived of sex and respect – and that drastic reassertions of male power are needed. It is, in effect, a virtual support group for patriarchal ressentiment. As one analysis puts it, the manosphere spans from broader male-supremacist discourse to more violent anti-women rhetoric, but all of it is misogynistic at core.

Incels and the Politics of Sexual Resentment

Perhaps the most disturbing subset of the manosphere is the incel subculture. Incels are heterosexual men who define themselves by their inability to obtain a sexual or romantic partner – and who consequently develop a hateful ideology blaming women (and societally empowered “alpha” males) for their plight. These are communities of sexual frustration curdled into extremist misogyny. On incel forums, one finds an astonishingly toxic brew of self-pity and vicious anger. Women are demonised as shallow creatures who only want to date attractive men (“Chads”), leaving “beta” men unfairly sexless. The incel worldview is openly zero-sum: they believe a finite amount of sex/affection exists, and women owe it to men; if certain men (the Chads) monopolise female attention, it is considered an injustice against the rest. This sense of entitled grievance has led to what even law enforcement labels misogynist terrorism.

Incels and the Logic of Deadly Violence

🇺🇸 The incel phenomenon first crashed into mainstream awareness in May 2014, when 22-year-old Elliot Rodger went on a killing spree in Isla Vista, California, murdering six people and injuring fourteen, then himself. Rodger left behind a 137-page manifesto and YouTube videos outlining his motivations: he saw himself as a supreme gentleman unjustly spurned by women, and he wanted revenge on the “blonde sluts” who wouldn’t date him and the sexually active men he envied. 9Jessica Valenti, Elliot Rodger’s California shooting spree: further proof that misogyny kills, 25 May 2014. In his final video, Rodger chillingly vowed to “punish” women for rejecting him and to “destroy” the joyful lives others were living.

This massacre was essentially an act of ideological violence – a warped crusade to restore what Rodger thought was the natural order (with himself on top, and women dutifully fulfilling male desires). Within incel and manosphere circles, Rodger was instantly canonised. On extremist forums, young men praised him as a “saint” and marked his birthday or the attack’s anniversary as “Saint Elliot’s Day.” They circulate memes of Rodger as an almost martyr-like figure, and even created tribute songs and T-shirts with his image. 10Ben Collins and Brandy Zadrozny, After Toronto attack, online misogynists praise suspect as ‘new saint’, 25 April 2018. If this sounds sick, that’s because it is – yet it is the logical endpoint of a hate-fuelled echo chamber where mass murder of women is valorised as a form of redress.

The internet doesn’t make hate, it monetises it.

Ian Danskin

🇨🇦 In 2018, self-described incel Alek Minassian ploughed a rented van into pedestrians in Toronto, killing 10 people. Minutes before, he had posted on Facebook: “The Incel Rebellion has already begun!… All hail the Supreme Gentleman Elliot Rodger!”. 11Gary Younge, Nearly every mass killer is a man. We should all be talking more about that, 26 April 2018. Minassian later told police he was radicalised in online incel groups and saw the attack as revenge for being a virgin in a world he felt rewards only others. Such incidents underscore that the manosphere is not just talk – its most extreme factions are incubating real-world violence.

From Normie to Extremist: The Radicalisation Pipeline

How does a young man become an incel or alt-right extremist? The process of digital radicalisation has been dissected by analysts and even illustrated in popular media (for instance, Ian Danskin’s video essay “How to Radicalize a Normie,” which breaks down the step-by-step recruitment of disaffected young men into the alt-right). The consensus is that the internet provides an ideal breeding ground for extremist conversion: algorithms funnel curious or vulnerable individuals toward ever more radical content, while anonymous message boards provide spaces to vent anger and find scapegoats for one’s personal failures. A teenager who feels lonely, emasculated, or bitter can easily stumble from a YouTube video about dating frustration to a misogynistic forum that validates his anger, then to a Discord chat with even more extreme members egging him on. Each click down the rabbit hole normalises ideas that would have seemed outrageous at first. The “normie” might begin by chuckling at sexist jokes on Reddit, but soon he’s on 4chan absorbing elaborate theories about how feminists ruin society – and from there it’s a short leap to praising Elliot Rodger or posting manifestos on incels.is.

Misogyny as a Gateway to the Far-Right

Crucially, the manosphere serves as a gateway to other reactionary ideologies. White nationalist and neo-fascist groups actively recruit from misogynist online spaces. The Institute for Strategic Dialogue notes significant cross-pollination between the manosphere and the broader far-right: neo-Nazi sites host “women = the Jews of gender” rants, while incel forums reference racist great-replacement tropes. In numerous instances, misogyny is the first hook – a young man’s entry point into hate – which then widens into racism and authoritarianism. It’s no coincidence that the 2017 Charlottesville rally organisers and many alt-right leaders first emerged from male-dominated forums like 4chan and Reddit. Misogyny has been called the “gateway drug” to extremism, and the pattern bears this out. Reflecting on the rise of the manosphere, researchers find that online boards focused on male insecurities and resentments can snowball into an ideology that serves as a route into wider far-right politics. 12Oxfam America, Masculinities and the Far-Right: Implications for Oxfam’s Work on Gender Justice, 30 October 2019. The common denominator is the appeal to aggrieved entitlement: “You deserve power/sex/status, and X (women, minorities, elites) conspired to rob you of it.” It’s a short hop from “women owe you sex” to “immigrants are replacing you” – both are zero-sum conspiracies targeting an Other.

The Authoritarian Temptation

The Frankfurt School scholars of the post-WWII era, such as Theodor Adorno and Erich Fromm, might not have predicted internet trolls, but they presciently analysed the authoritarian personality type that finds refuge in such movements. Isolated, alienated individuals, they observed, often develop rigid, authoritarian attitudes as a psychological escape from uncertainty – craving clear hierarchies and someone to blame for their frustrations.

Adorno described how those with repressed hostilities and strict upbringing could become submissive to authority above them, but cruel to those below (scapegoating out-groups). Incel and alt-right subcultures exhibit a version of this: members alternating between self-loathing passivity and vicious aggression toward scapegoats.

Fromm warned in Escape from Freedom (1941) that when people feel powerless and free-floating, they may seek security by surrendering to authoritarian movements and projecting their insecurities outward as hatred. The manosphere is essentially an authoritarian temptation for the lost young man: it promises him that by embracing a reactionary, hyper-masculine ideology (and perhaps a charismatic internet demagogue or two), he can reclaim control and identity.

Conclusion: Patriarchal Grievance as Political Force

In sum, the manosphere and incel culture reveal patriarchal insecurity at its rawest. Here are men who feel utterly left behind in a changing world – economically precarious, socially adrift, romantically rejected – gathering in digital enclaves that validate their pain but channel it toward destructive ends. Through constant peer reinforcement and algorithmic nudging, their personal grievances harden into extremist ideology. A so-called “Beta Uprising” against society starts to seem reasonable to them, even heroic. It is a tragic feedback loop: the more they wallow in misogyny and self-pity, the more they alienate themselves from the very society they feel wronged by, which only deepens their isolation and anger. Thus, radicalisation accelerates. Understanding this dynamic is essential because it links the lone-wolf attacker in one context to broader reactionary currents in others. The same insecure masculinity that drives an incel to kill can drive masses of men to vote for an authoritarian strongman or to join a mob attacking a capitol. The scale and expression differ, but the root – aggrieved patriarchal entitlement – is the same.

Andrew Tate, Hustlers & Loverboys: Patriarchal Capitalism Online

Alpha as Algorithm: The Rise of Hustler Masculinity

If incels represent one toxic coping mechanism for emasculation (retreating into self-described victimhood and lashing out violently), figures like Andrew Tate represent another: doubling down on patriarchal dominance through a caricature of capitalist success.

Andrew Tate – the former kick boxer turned social media influencer – is a poster child for what we might call hustler hyper-masculinity. Through flashy cars, money, cigars, and bikini-clad women, Tate markets an image of manhood restored to its primitive throne: the man as alpha entrepreneur and unabashed sexist, who bends both women and money to his will. His catchphrases and videos explicitly tell young men that the route to happiness is through exerting power – financial and sexual – over others. Notably, Tate dubbed himself the “king of toxic masculinity” and a “misogynist influencer”, almost relishing the outrage he caused. 13Patrick Reevell, Andrew Tate, ‘King of Toxic Masculinity,’ faces 3 legal cases in 2 countries, 21 May 2024.

He gained millions of followers (particularly teen boys) with viral TikToks that mixed self-help bromides (“go to the gym, grind for success”) with vile misogyny (“women are property,” “if your girlfriend has Instagram, that’s cheating”). In Tate’s worldview, male supremacy is not something to hide – it’s a brand. And countless young men, feeling starved for a sense of power and identity, eagerly consumed that brand.

Monetising the Grind: Selling Insecurity as Lifestyle

Tate’s rise also illustrates the commodification of patriarchal identity. He literally monetised male insecurity via subscription platforms like “Hustlers University,” where subscribers (mostly young men) paid monthly fees for supposed lessons on getting rich and getting girls. In essence, he was selling an identity product: the fantasy of becoming a high-value alpha male like Tate himself.

This is patriarchal capitalism on steroids – taking the oldest tropes of male dominance and repackaging them as a purchasable online service. French social theorist Michel Foucault might have noted how Tate’s enterprise reflects disciplinary power in a new form: young men subject themselves to Tate’s diktats on how to behave, dress, think, and even feel (ridiculing any display of emotion or weakness) in order to transform themselves into the “ideal” man. It’s a self-policing regimen, much like Foucault’s concept of discipline, but delivered via YouTube videos and Telegram chats. The panopticon is now a WhatsApp group where thousands of acolytes report their daily adherence to the grindset.

From Influencer to Predator

But Tate’s brand of masculinity is not only performative – it’s predatory. In 2023, he and his brother Tristan Tate were indicted in Romania on charges of human trafficking, rape, and forming an organised crime group. Romanian prosecutors allege the Tates used the “loverboy” method to recruit young women: seducing them with false promises of love and marriage, then coercing them into sex work (specifically, into performing on webcam sites) for the Tates’ enrichment. 14Sky News, Andrew Tate’s home raided amid new claims of trafficking minors, 21 August 2024.

The loverboy technique is a known method in human trafficking circles: a manipulative romance scam that lures victims into exploitation. That the self-styled king of male empowerment has been accused of literally enslaving women for profit is, in a way, the ultimate reveal of what his philosophy entails. Tate’s hustler masculinity treats women as commodities to be monetised – either indirectly (as status symbols in his Instagram posts) or directly (through sex trafficking and pornography). It is patriarchal capitalism laid bare: women’s bodies become sites of accumulation, and masculinity is measured by one’s ability to amass wealth and control by any means necessary. Tate has denied the charges, but according to Romanian investigators, his operation was essentially organised crime under a veil of influencer glamour.

The same fans who watched him puff cigars and preach male dominance in videos were inadvertently getting a glimpse of how far that dominance might go in practice – right into the realm of coercion and violence.

A Global Hustler Archetype

While Tate himself is a particularly egregious example, he is not alone. Across cultures, there are parallel figures and subcultures promoting a similar hustler macho ethos. These range from American pickup artists selling $1,000 courses on how to psychologically manipulate women into bed, to Nigerian Instagram stars flaunting wealth and misogyny, to young British men on TikTok peddling crypto-trading schemes alongside anti-feminist rants.

All share a core message: Real men get rich and get women (and if you aren’t, it’s women’s fault or your own weakness). Women in these narratives exist to be conquered – sexually and financially. This attitude revives the old patriarchal notion of women as property, but updates it for the digital age of global capitalism.

As one Nigerian Twitter user quipped ironically, “The broligarch’s creed: get money or die trying – and make sure she cooks while you do.” Indeed, the “hustler” influencers often reduce women to servants or ornamental rewards, as if auditioning for a 1950s time-travel fantasy.

Capital, Control, and the Commodification of Gender

Philosophically, one can view this through Foucauldian and Marxist lenses. Foucault wrote about biopower: the management of bodies and populations in modern regimes of power. Figures like Tate exert a privatised biopower: disciplining not an entire population, but a coterie of followers and a harem of exploited victims. They turn human relations into hierarchies of control, where the influencer is the sovereign and others are instruments. Meanwhile, Marxist theory would note how the commodification of everything under capitalism extends even to gender relations.

Under neoliberal logic, masculinity itself becomes a commodity (to be packaged by influencers), and female sexuality becomes an input for entrepreneurial ventures (webcam studios, OnlyFans “management” agencies, etc.). It’s telling that in Tate’s leaked chats with associates (as reported in court documents), women were referred to in cold economic terms – discussing their “output,” how to maximise their earnings on cam, how to maintain control over them via debt or emotional manipulation. This is patriarchy converging with late capitalism’s transactional ethos.

Even romantic relationships are reduced to the terms of exchange: the man provides luxury or promises; the woman provides sex. Love is entirely absent, a useless concept in this power calculus.

Beneath the Swagger: Fear of Irrelevance

The loverboy/hustler model of masculinity also reveals a great deal about insecurity. After all, a truly secure man would not need to boast constantly about his conquests or entrap women to prove his dominance. The bravado of the hustler covers a fear that without wealth and women, he is nothing. It’s poignantly ironic: these men define their worth by the very validation of women (sexual availability, physical attractiveness) that they loudly claim to scorn.

In psychological terms, this is textbook overcompensation – a feedback loop of insecurity fuelling abusive behaviour, which in turn masks the insecurity for a while, until it grows bigger and demands even more domination to keep at bay.

Andrew Tate’s alleged crimes can thus be considered an extreme attempt to freeze an unequal power dynamic in place—because he cannot tolerate a world where women might freely choose to leave him. The ‘lover-boy’ turns violent when the illusion of voluntary devotion doesn’t hold. This brutality is the logical (if horrific) end of the hustler mindset: when charm fails, impose your will by force.

Conclusion: Predation with Product Placement

In the end, the rise of figures like Tate isn’t always cloaked in victimhood or tradition – sometimes it wears a flashy Rolex and quotes Jean-Paul Sartre. It attracts young men’s angst: don’t be weak, become a top G (to use Tate’s slang) by embracing greed, aggression, and misogyny. It offers a fantasy of dominance for those who feel emasculated, and it has spread globally through social media.

The challenge society faces is that this hustler machismo is not merely braggadocio – it actively cultivates domination and criminality. It glamorises a worldview that is fundamentally anti-democratic and predatory. Thus, confronting it requires not just debunking its pseudo-advice on “what makes a man,” but also delegitimising the broader equation that wealth and women are what make a man.

Until alternative visions of male success and self-worth are made more visible and compelling, the Andrew Tates of the world will continue to find an eager audience of men searching for an armour to don against their insecurities.

Anti-Wokeness & Reactionary Cultural Backlash

Defining the Anti-Woke Reaction

Parallel to the gender-focused backlash, recent years have seen the rise of a broad anti-woke movement: a reactionary cultural backlash against progressive values in multiple arenas. “Wokeness” (initially African American slang for social awareness) has been co-opted as a catch-all pejorative used by reactionaries to denounce everything from racial justice protests to LGBTQ+ inclusion to feminist advocacy. To be “woke”, in the reactionary lexicon, is to be a shrill, tyrannical enforcer of liberal change – an enemy of tradition, free speech, and supposedly common sense. Thus, anti-wokeness fashions itself as a defence of the proverbial Everyman (often coded as the straight white male Everyman) against an oppressive new orthodoxy of political correctness. In practice, it often amounts to punching down at marginalised groups under the banner of fighting elitism.

Backlash Across Borders

This cultural counter-revolution is not just rhetorical. Around the world, it has manifested in elections and policies.

🇧🇷 In Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro rode to power on a wave of anti-left, anti-“gender ideology” sentiment, vowing to restore traditional family values and railing that Brazil’s problems stemmed from feminism and LGBTQ+ rights. He infamously dedicated his UN speech to attacking “gender ideology” and joking that Brazil had too many human rights (which he claimed protected only criminals and perverts). His government’s crusade against what he called “cultural Marxism” led to crackdowns on academic freedom and the defunding of gender studies programs. 15AFP, New Brazil government drops ‘diversity’ from school books, 9 January 2019.

🇭🇺 In Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has explicitly framed himself as leader of an international movement against “woke culture.” At the 2022 Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in Budapest, Orbán declared liberalism a “virus” and hung a giant banner reading “NO WOKE ZONE” over the entrance. 16Flora Garamvolgyi, Hungary’s far-right PM calls for Trump’s return: ‘Come back, Mr President’, 4 May 2023. He boasted that Hungary is an “incubator” for conservative policies fighting “progressive elites”. Orbán’s government has enacted laws banning depictions of LGBTQ+ people to minors and essentially equating homosexuality with paedophilia – all justified as protecting the nation’s Christian values from decadent Western liberalism.

🇹🇷 In Turkey, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has similarly leaned into culture-war rhetoric: ahead of elections he thundered “We are against the LGBT” at rallies, positioning himself as the guardian of the sacred family unit. 17Ruth Michaelson and Deniz Barış Narlı, ‘We’re against LGBT’: Erdoğan targets gay and trans people ahead of critical Turkish election, 12 May 2023. He even accused opposition parties of being “LGBT” simply for not vilifying queer people.

🇷🇺 In Russia, Vladimir Putin ramped up anti-woke, anti-LGBTQ rhetoric to fever pitch after 2020, casting Russia as the bastion of “traditional family values” versus a West that has “fallen into moral depravity.” In 2022, amid the Ukraine war, the Kremlin pushed through an expanded law banning all “LGBT propaganda” among adults – effectively criminalising any positive mention of same-sex relationships. 18Human Rights Watch, No Support. Russia’s “Gay Propaganda” Law Imperils LGBT Youth, 11 December 2018. Putin’s speeches increasingly frame his geopolitical aims as a civilisational battle against the “open satanism” of Western liberal gender norms.

The Engine of Moral Panic

What unites these examples is the narrative of moral panic – a classic Stanley Cohen concept wherein a societal change or minority group is exaggerated into a dire threat to social order. Here, “wokeism” is the folk devil. Anti-woke crusaders paint a picture of a world turned upside-down: children being indoctrinated with degenerate ideas, men being emasculated, freedom of speech under assault by intolerant progressives. This narrative has been extremely potent for mobilising a conservative base that feels disoriented by rapid social changes. Sociologist Susan Faludi, in her 1991 book Backlash, documented how every wave of feminist progress in the 20th century was met with a counter-wave of scare stories and repressive measures aimed at reasserting patriarchal control. We are seeing a similar backlash today not only to feminism but to the broader egalitarian gains of recent decades (multiculturalism, LGBTQ+ visibility, etc.). The zero-sum thinking is palpable: if gay or trans people can freely exist, then our children are at risk; if ethnic minorities get a seat at the table, our heritage is being erased; if women assert boundaries, our freedoms as men are somehow curtailed. In reality, none of these things are zero-sum – rights are not a finite resource – but backlash politics thrives on the emotional logic of loss and grievance.

Asymmetric Warfare: Going Low to Win

Ian Danskin’s video “You Go High, We Go Low” in The Alt-Right Playbook series offers a keen insight into how reactionaries exploit the norms of liberal tolerance. He notes that right-wing provocateurs intentionally push the envelope of hateful speech or actions knowing that progressives face a dilemma: either respond forcefully (and be painted as illiberal censors), or do nothing (and let the hate flourish). By painting any response besides quiet, peaceful protest as unacceptable, the right effectively forces progressives to “play by the rules” while they themselves wage a no-holds-barred fight. This asymmetry has been evident in many cultural clashes.

For example, far-right figures hold rallies or campus speeches deliberately to provoke outrage; when students or activists protest loudly, conservative media portrays the protesters as the problem – illiberal, violent, and “too woke.” Meanwhile, the substantive issues (racism, sexism, homophobia being platformed) get sidelined. As Danskin puts it, the right forces progressives into a defensive crouch, afraid to be seen as uncivil or intolerant, which often leads to inaction or purely symbolic gestures. This tactic—never play by your opponent’s rules of decorum—allows reactionaries to go low (spread lies, hate, and fear) while their opponents are constrained by the imperative to go high (remain polite, factual, and calm). In country after country, we’ve seen liberal parties and institutions struggle with this dynamic, frequently ceding cultural ground as a result.

Collateral Damage: Human Costs of the Backlash

🇵🇱 The anti-woke backlash has real human costs. Its targets are not abstract concepts but vulnerable groups. Consider Poland’s right-wing government, which embraced anti-“gender ideology” and anti-abortion positions in line with this backlash. In 2020, Poland’s authorities imposed a near-total abortion ban (under pressure from ultraconservative Catholic groups), framing it as a victory for traditional values. The result? Multiple pregnant women have died in Polish hospitals in the past two years because doctors, fearing prosecution, refused to terminate non-viable or life-threatening pregnancies in time. 19Human Rights Watch, Poland: Abortion Witch Hunt Targets Women, Doctors, 14 September 2023. These women became martyrs of a reactionary policy that valued an ideological notion of fetal rights and female chastity over real women’s lives.

🇺🇸 In the United States, a similar anti-woke/anti-feminist strain fuelled the reversal of Roe v. Wade in 2022, leading to immediate suffering as women in many states lost access to healthcare. In Brazil under Bolsonaro, incendiary anti-LGBTQ rhetoric from the top emboldened street-level violence against queer people and gave police cover to harass LGBTQ+ gatherings.

🇭🇺 🇷🇺 In Hungary and Russia, state-sponsored homophobia has created climates of fear for LGBTQ+ individuals – families are fleeing these countries because raising a queer child or simply living openly has become dangerous.

🇹🇷 “We’re dealing with a hazardous environment, where women and LGBTQ people are attacked,” said one Turkish activist on the atmosphere Erdoğan’s rhetoric has stoked. 20Ruth Michaelson and Deniz Barış Narlı, ‘We’re against LGBT’: Erdoğan targets gay and trans people ahead of critical Turkish election, 12 May 2023. The backlash uses the language of “family” and “safety” to justify policies that make many families less safe, especially those that don’t fit the traditional mould.

Culture War as Cover

🇷🇺 It’s also important to note that anti-woke backlash is often a smokescreen for power grabs. Authoritarian-leaning leaders flog cultural issues to consolidate political support and distract from other failings. Putin’s regime, faced with economic stagnation and war setbacks, doubled down on anti-LGBT propaganda to rally conservatives at home.

🇺🇸 In the US, politicians have weaponised “critical race theory” and trans participation in sports as wedge issues, whipping up their base’s emotions while avoiding topics like healthcare or income inequality. This pattern harks back to an old strategy: stoking moral panic to justify authoritarian measures. In the 1980s, the bogeyman might have been satanic cults or “welfare queens”; today it’s drag queens reading books to children or ethnic studies curricula. The specifics change, but the formula is the same. By manufacturing a crisis (the nation’s morals under siege), reactionary forces can present themselves as saviours and implement their agenda with less resistance.

🇭🇺 For instance, Hungary’s Orbán has used the pretext of “defending Christian values” to erode press freedom and judicial independence, skirting greater EU backlash by cloaking authoritarian moves in the language of culture war.

Culture wars never end peacefully—they simply change battlefields.

Someone, somewhere.

Masculinity Reloaded

This cultural backlash often intertwines with the machismo discussed earlier. It glorifies a return to a simpler social order where men are men, women know their place, and outsiders remain marginal. Brazil’s Bolsonaro revelled in a crass, hyper-masculine persona – he once told a female lawmaker she “didn’t deserve” to be raped by him, implying she was too ugly. Such grotesque machismo was shrugged off by his supporters as straight talk. In their eyes, Bolsonaro’s refusal to “go high” was precisely the appeal – he would go low and fight dirty against the liberal establishment. We see echoes of this in American politics, where figures like Donald Trump and his imitators proudly violate norms of civility (insulting women’s appearances, mocking disabled reporters, using racist dog whistles) and are adored for it by followers who view “political correctness” as the true evil. The anti-woke hero is, essentially, the anti-hero who breaks the polite rules. This taps into a kind of nihilistic glamour: the outlaw ethos repurposed for cultural reactionaries. It’s a perverse inversion – intolerance sold as a form of rebellious courage.

Conclusion: Fear in the Language of Freedom

In summary, the anti-woke backlash is the cultural front of the reactionary resurgence. It operates by demonising social justice movements and casting any effort to broaden rights or empathy as an existential threat to the majority’s way of life. It mobilises patriarchal and nationalist insecurities (about gender roles, national identity, religious orthodoxy) under a unified banner: “Enough with this woke nonsense!” This backlash reveals that progress is not linear – gains toward inclusion can provoke fierce regression. Its success in various countries demonstrates how easily fear and resentment can be channelled into political ends. And it underscores a key point of our thesis: whether the issue is gender, sexuality, or race, the reactionary mindset reduces it to a zero-sum clash. If “they” gain dignity or visibility, “we” lose ours. It is precisely this worldview we must confront to break the cycle of backlash.

Transactional Politics & Broligarchy Globally

Enter the Broligarchy

Beyond culture and internet subcultures, reactionary dynamics have also reshaped governance in many countries – giving rise to what one might call a “broligarchy” of transactional politics. The term broligarchy (a portmanteau of bro and oligarchy) was initially coined to describe rule by a clique of wealthy, tech-oriented men – essentially, Silicon Valley plutocrats exercising outsized influence. But in a broader sense, it captures a style of governance visible in figures like Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin, and others: a swaggering, male-centric oligarchy where informal networks of “bros” (cronies, business tycoons, old boys from elite circles) scratch each other’s backs, and politics is approached as a series of transactional deals rather than a process of deliberation or public service.

The Bro Regimes

In these “bro” regimes, personal loyalty often trumps institutions. Leadership is chest-thumping and performative (think of Duterte’s profane tirades or Berlusconi’s playboy antics). There is a machismo not just in cultural attitude but in the very conduct of politics: an embrace of ruthlessness, a disdain for the rule of law or procedural niceties, and an ethic that winning (money, power, elections) justifies any means. It’s as if the fraternity house took over the legislature – complete with locker-room talk, impulsive decision-making, and occasional criminal hazing rituals. Transactional politics here means that everything is up for negotiation (or sale) among the in-group of powerful men. Policies are not driven by ideology so much as by quid pro quo: support my bid or business, and I’ll reward you; cross me, and you’re out.

🇮🇹 Consider Berlusconi’s Italy. As Prime Minister, Silvio Berlusconi famously blurred the line between state and personal enterprise – he appointed showgirls from his TV channels to government posts, hosted world leaders at his private villas where escorts mingled with diplomats, and treated parliament like an inconvenience to be bypassed via decree when possible. His style was ultra-macho: crude jokes, hair transplants, and the unapologetic nickname “Il Cavaliere” (The Knight). He created a cult of personality where loyalty to him mattered far more than party or principle. Under Berlusconi, Italian governance often boiled down to deals struck between powerful men at private dinners.

🇺🇸 Similarly, Donald Trump’s administration in the U.S. had strong broligarchic tendencies. Trump, a businessman with no public sector experience, ran the White House like a family business. He gave key roles to his children; he publicly praised authoritarians as his “friends” and pursued foreign policy via personal favours (e.g., extorting Ukraine for dirt on a rival, as detailed in his first impeachment). His decision-making was driven by ego, loyalty tests, and transactional thinking – for example, openly suggesting he deserved favours from states to whom the U.S. provides aid. The concept of public duty was often absent; instead it was, “What can you do for me?” (One might recall his telling remark: “I need you to do us a favour, though” – conflating personal political favours with national interest.)

Oligarchs play chess, broligarchs flip the board.

Political satirist, anonymous.

🇬🇧 In the UK, Boris Johnson, though very different in personality, similarly presided over a ‘chumocracy’ of cronies. Johnson’s government saw multiple scandals of contracts awarded to friends, ethical rules bent for allies, and an overwhelming sense that truth and rules were malleable if you were part of the Old Boys’ club from Eton and Oxford. Johnson himself often shrugged off misconduct (his or others’) with a jovial bluster, refusing to play defence. Indeed, he almost never admitted fault; instead he would distract or double down, exemplifying the “never play defence” strategy common to these leaders. As Ian Danskin observed in Never Play Defence, the idea is to always go on the offensive when accused, never apologise – an approach Johnson took to extremes by attempting to prorogue Parliament illegally and later partying through COVID-19 lockdowns and initially denying it. The broligarchy ethos told him rules are for lesser folks.

🇵🇭 In places like the Philippines under Rodrigo Duterte, the bro style took a violent turn: Duterte literally encouraged police and vigilantes to execute suspected drug dealers, bragging about doing the same in his youth. He revelled in a Dirty Harry image, dismissing human rights as pesky hurdles. He stacked his cabinet with retired generals and drinking buddies. Patronage and intimidation replaced any semblance of due process. The transaction here was clear: Duterte promised security (through brutality) in exchange for unchecked power.

Tech Bros and Populist Alliances

🇺🇸 One striking example of broligarchy on the world stage has been the courtship between populist politicians and tech billionaires – merging political and economic “bros” into a new ruling clique. In the United States, the South African tech moguls like Peter Thiel and Elon Musk threw their weight behind Trumpian candidates. Thiel, a billionaire who co-founded PayPal, became a major backer of Trump and other far-right figures (he funded J.D. Vance, an acolyte who ended up in the Senate). Elon Musk, after years of affecting political aloofness, started to openly embrace anti-woke rhetoric and signal support for right-wing causes. By 2024, Musk was fraternising with Republican leaders and reportedly offering to pour enormous sums into the election on their behalf. Carole Cadwalladr, investigating this, called it the alliance of the tech broligarchs with political reactionaries. 21Carole Cadwalladr, How to survive the broligarchy: 20 lessons for the post-truth world, 17 November 2024. One might say the world’s richest bro (Musk) and the world’s most powerful bro (Trump) recognised each other as kindred spirits. Both see themselves as rule-breaking disruptors who disdain “woke” elites and like to communicate via tweets (now X posts) and memes. The convergence of interests is clear: tech oligarchs get deregulation and influence, while populist politicians get money and platforms. The result is a kind of oligarchic populism – superficially contradictory, but in practice a dominant mode in many countries. (In Russia, Putin perfected this by empowering oligarchs as long as they remained loyal and served his nationalistic agenda, essentially creating a fraternity of billionaires who sponsor and benefit from his rule.)

Authoritarian Neoliberalism

The neoliberal economic order of recent decades also dovetails with broligarchy. Neoliberalism, with its emphasis on deregulation, privatisation, and “deal-making” over social welfare, creates an environment where transactional relationships thrive and where wealthy insiders can capture outsized benefits. Authoritarian populists often ride to power by criticising the neoliberal elite, but once in power, they frequently govern in a neoliberal (or crony-capitalist) way themselves – handing state resources to favoured business allies, cutting taxes for the rich, weakening labour protections. This isn’t a bug; it’s a feature of bro-politics. Their primary allegiance is to their in-group (fellow tycoons, political loyalists) and maintaining dominance, not to any left-right economic dogma.

🇮🇳 For instance, Narendra Modi in India combines Hindu nationalist rhetoric with policies friendly to big business (witness his closeness with industrialist Gautam Adani). Putin railed against 1990s oligarchs but ended up establishing a new oligarchy under his patronage.

🇺🇸 In the U.S., Trump decried globalist elites but passed massive corporate tax cuts and stocked his cabinet with former Goldman Sachs bankers.

The upshot is a form of authoritarian neoliberalism: the free market for the cronies, authoritarian control for the masses. Foucault’s concept of governmentality – how governments produce citizens who conform to certain norms – can be applied here: broligarchs shape a citizenry (or at least a voter base) that accepts corruption and brute force as normal as long as the in-group (the “real people” of the nation) seem to benefit or get revenge on the “outsiders.” It’s a perverse social contract: let us run the state like our private club, and we will protect your cultural interests or make the trains run on time.

Masculinity as Method

This transactional bro governance erodes democratic norms. Independent institutions (courts, media, electoral commissions) are seen as pesky or hostile if they check the leader’s deals, so they are undermined. Duterte jailed critics and packed courts; Bolsonaro attempted to intimidate Brazil’s supreme court and spread fraud conspiracy theories preemptively; Trump literally tried to subvert a democratic election when the transaction (the vote) didn’t go his way, inciting a mob attack on the U.S. Capitol. “Never play defence” indeed – these leaders will break the system rather than admit defeat within it.

The bro creed values winning above all, so losing (or being held accountable) is an existential threat. Hence, the alarming trend of democratic backsliding into competitive authoritarianism in many of these cases. They hold elections but undermine fairness; they have a judiciary but try to capture it; they face media criticism but drown it in disinformation and loyalist propaganda.

One can also view broligarchy as a mutation of patriarchy for the modern era. It is patriarchal in that it’s overwhelmingly male-dominated, valorises traditionally masculine traits (strength, dominance, deal-making prowess), and often explicitly seeks to keep women (and other “outsiders”) out of power. Many bro-type leaders have a dismissive or hostile attitude toward female authority. (Recall Boris Johnson’s history of sexist quips, or Berlusconi’s open objectification of women, or Trump’s inability to hide his contempt when debating female opponents.)

When women do rise in these systems, it’s often through being adopted into the bro network (e.g., a daughter like Ivanka Trump, or a trusted surrogate who mimics the boys’ club ethos). The “old boys’ network” long spoken of in corporate contexts has effectively seized the state apparatus in these cases. And just as feminists have criticised that network in business for shutting out women and minorities, in governance its consequences are severe: policies that ignore or harm those not in the club. It’s telling, for example, that during COVID-19, several macho populist leaders (Trump, Bolsonaro, Johnson, Modi) were notably cavalier with human life, delaying responses or peddling quack cures.

Empathy – stereotyped as a “feminine” trait – was scant. The idea of collective care was downplayed; instead it was macho bravado (“it’s just a flu,” “we won’t let it stop our freedom”) and, in some cases, brutal triage when things got bad. A broligarchy does not nanny its people; it bro-handles them, which can mean neglect or coercion but rarely compassionate governance.

Life Inside the Club

From a citizen’s perspective, living under a broligarchy feels like being a spectator to a rigged game. Ordinary people see leaders flout rules with impunity (Partygate in the UK, for instance, where Johnson’s team held lockdown parties the public was barred from – one rule for them, another for us). They see corruption dealt with via slaps on wrists or pardons (Trump pardoned loyal cronies convicted of crimes). They might sense that unless you’re connected or can offer something, your voice means little – because everything’s transactional.

This breeds cynicism and disengagement among the public, which ironically helps the broligarchs consolidate power further (a demoralised public is less likely to mobilise against corruption or authoritarian drift). Thus, bro politics can be self-perpetuating, creating an apathy that allows more brazen behaviour. Each scandal wears people out until scandal becomes the new normal.

Never Play Defence

To tie back to Danskin’s Alt-Right Playbook, one episode is titled “Never Play Defence.” That mantra encapsulates how broligarchs operate. They do not earnestly answer critics or step back when conflict of interest is exposed. They go on the offensive – sacking investigators, smearing whistleblowers, launching new controversies to divert attention.

Steve Bannon famously said the Trump team’s tactic was to “flood the zone with shit,” meaning overwhelm the media with so much outrageous content that focus and accountability become impossible. This strategy has intellectual roots in authoritarian populism, but also resonates with game theory: the best defence is a good offence. The public, overwhelmed and confused, eventually tunes out or throws up its hands. The net effect is that wrongdoing goes unpunished and the norms gradually reset around a lower standard of integrity.

Conclusion: Frat-State Authoritarianism

In summary, the global broligarchy trend demonstrates how patriarchal-authoritarian impulses have infused governance in the 21st century. These leaders and their coteries turn politics into a macho arena of deal-making, chest-thumping, and norm-breaking. They appeal to those tired of cautious technocratic politics, offering instead the thrill (and risk) of “manly” leadership – leadership that is personal, unrestrained, and unapologetically self-interested. It is a rejection of enlightenment ideals of impersonal rule of law in favour of a quasi-feudal return to l’état, c’est moi of Louis XIV, the self-proclaimed ‘Sun King’.

The implications for democracy are dire: when the government becomes a frat party for billionaires and demagogues, everyone outside the house is at best a pawn, at worst an enemy. In the next section, we delve deeper into the zero-sum worldview that underpins such thinking, linking it explicitly to nationalist and xenophobic politics across the globe.

Zero-Sum Worldview as a Philosophical Core

The Zero-Sum Illusion

Running through all these reactionary phenomena is a distinctive Weltanschauung: a zero-sum worldview. This is the belief that social life is a fixed pie – any gain by one group must come at a direct loss to another. It’s an inherently adversarial, Hobbesian outlook, seeing society not as a cooperative project but as an ongoing struggle in which one’s group must fight to maintain or expand its share of power. The zero-sum mindset is evident in how reactionaries frame every issue.

- Women getting rights? That means men losing status or opportunities.

- Minorities getting representation? That means the majority’s culture is being erased.

- Refugees being welcomed? That means resources or safety for natives are diminished.

In this view, equality is not a win-win ideal – it’s a threat, a demand that those on top surrender something. As Nietzsche might put it, those with a zero-sum mindset cannot imagine a master without a slave; if they are not unequivocally on top, they feel they must be on the bottom.

Replacement Fantasies and Nationalist Paranoia

In far-right circles, this zero-sum thinking often takes the form of ethno-nationalism and the notorious “Great Replacement” conspiracy theory. White nationalist ideologues in Europe and the US propagate the idea that non-white, non-Christian immigrants are “replacing” the native (white) population – literally swapping them out over time. It’s a paranoid reframing of demographic change as an apocalyptic race-war scenario.

🇫🇷 In France, for example, Marine Le Pen and her National Rally (formerly National Front) traffic in the narrative that “multiculturalism has failed” and that France must undertake a “de-Islamisation” to survive. 22Peggy Hollinger, Le Pen daughter applauds Cameron, Financial Times, 9 February 2011. Muslims in this view are a sort of invading army – even if they’ve been French for generations – and every increase in their visibility or numbers is portrayed as an existential peril to Frenchness. The logical endgame of this view is indeed zero-sum: either we dominate them or they dominate us. There is no concept of pluralism or shared civic nation; it’s a demographic tug-of-war.

🇩🇪 This rhetoric has found fertile ground in Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) as well. After incidents like crimes by asylum seekers, AfD figures like Björn Höcke exploit the situation by asking Germans, “Do you really want to get used to these conditions? End the misguided experiment of multiculturalism!”. 23Hanno Hauenstein, The AfD has stunned Germany – but this was no surprise victory, 2 September 2024. The insinuation is clear: immigrants = chaos and crime; the only solution is to purge or totally suppress the immigrant presence. Within hours of a knife attack by a foreigner, calls for mass deportations flood German discourse. Even establishment politicians, fearing the zero-sum populist surge, started echoing those narratives about deportation as a security measure. Thus, the frame shifts to Germans vs. immigrants, rather than focusing on, say, integrating communities or addressing crime in a nuanced way.

Scapegoats and Sectarianism

🇮🇳 In countries with deep racial or ethnic divides, the zero-sum lens is unfortunately familiar. Hindutva ideology in India explicitly posits India as a Hindu nation where other groups (Muslims, Christians) are guests at best, enemies at worst. The ruling BJP’s rhetoric often implies that if Muslims gain any political power or cultural space, it is an erosion of Hindu primacy. “If you’re not pro-government, you’re anti-national” – this extreme formulation by Modi’s right-hand man encapsulates how dissent (often by minorities or liberals) is framed as betrayal. 24Sunaina Danziger, Dividing Lines: What India’s Hindu Nationalist Turn Portends For Relations With Pakistan, 19 June 2020. The Modi government has indeed “cultivated a zero-sum nationalism” in which Muslims are told to “go to Pakistan” if they don’t like their second-class status. In practical terms, this has meant laws like the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) of 2019, which pointedly fast-tracks citizenship for non-Muslim refugees while excluding Muslims – the first explicit legal religion-based discrimination in India’s citizenship law. It also meant the revocation of autonomy in Kashmir, India’s only Muslim-majority state, and subsequent lockdowns and mass detentions. These moves are celebrated by Hindu nationalists as victories for Hindus, asserting dominance over Muslims. The satisfaction stems from a perceived zero-sum gain: we took something from them, so we are stronger. It hardly matters that these policies also harm India’s democracy and social fabric; what matters in the zero-sum logic is who’s on top right now.

🇿🇦 In multiethnic societies under strain, we see similar patterns. In South Africa, where xenophobic sentiments against foreign African migrants have sporadically flared into violence, many locals in poor townships believe (falsely, but fervently) that immigrants are the direct cause of their unemployment and insecurity. Populist politicians there push a narrative that undocumented migrants “are responsible for crime, drug peddling, unemployment, and other problems” and that “they must go home”. 25Human Rights Watch, South Africa: Toxic Rhetoric Endangers Migrants, 6 May 2024. This despite economic studies showing immigrants often create jobs and that structural issues drive unemployment. But zero-sum thinking is allergic to structural analysis; it zooms in on a convenient scapegoat. Foreigners become the folk devil onto whom all woes are projected, and expelling or harming them is seen as benefiting natives, almost axiomatically. The toxic chorus “We don’t want illegal foreigners here” has led to deadly pogroms in Johannesburg and Durban. Xenophobic mobs literally chant slogans like “Put South Africans first!” as they loot and burn immigrant-owned shops. The promise of a simplistic gain (jobs for locals once foreigners are gone) motivates horrific violence. And when such violence occurs, some political leaders either silently condone it or issue tepid statements, careful not to alienate the xenophobic voter base. It’s a deadly feedback loop of zero-sum paranoia.

The Fear of Inversion

The authoritarian personality mindset discussed earlier dovetails with zero-sum outlooks. If one believes the world is a hierarchy of domination, then any rise of “the other” feels like a direct challenge to one’s own group’s position – a potential reversal of roles. Theodor Adorno noted how in prejudiced individuals, there’s often a deep fear of status inversion (the master becoming the slave). Nietzsche’s concept of master-slave morality can be inverted here: the reactionaries see themselves as rightful masters under siege by slave rebellion. Therefore, they cling harder to master morality – celebrating strength, conquest, and exclusivity – and vilify “slave morality” which they associate with egalitarianism or empathy.

It’s telling how often reactionary rhetoric scorns compassion or “softness” as enabling the other’s rise. For instance, European far-right discourse typically complains that liberal tolerance and humanitarianism have made their nations weak, allowing migrants (often derided as inherently aggressive or fecund) to exploit that weakness. This echoes the Nietzschean disdain for the meek. The far-right French writer Renaud Camus (who popularised the Great Replacement theory) frames it almost as a law of nature: either you dominate demographically or you will be dominated. This stark binarism is deeply zero-sum and has inspired multiple white supremacist terrorists (e.g., the Christchurch shooter in 2019 titled his manifesto “The Great Replacement” and explicitly referenced Camus’s ideas). 26Joe Heim and James McAuley, New Zealand attacks offer the latest evidence of a web of supremacist extremism, Washington Post, 15 March 2019.

When you’re accustomed to privilege, equality feels like oppression.

Shaun King

The American Case: From Anxiety to Reaction

Even in countries without large immigrant inflows, internal zero-sum narratives take hold. Take the United States: segments of the white population, encouraged by right-wing media, perceive policies like affirmative action or even basic diversity and inclusion efforts as anti-white “discrimination.”

A striking example was during the presidency of Barack Obama, when many whites came to feel they were now the most oppressed group in America. (Polls showed significant numbers believed anti-white bias was a bigger problem than anti-Black bias!) This, despite whites still dominating wealth and power. The only “loss” whites experienced was the psychological one of seeing a Black family in the White House and hearing more public discussion of racism.

Yet through a zero-sum lens, many inferred that if a minority group is ascending in status, the majority must be descending. This set the stage for Donald Trump’s explicitly race-baiting campaign in 2016, which spoke to white anxieties about becoming a minority (the U.S. Census projections show whites will dip below 50% of the population around 2045). Trump’s slogan “Make America Great Again” carried the subtext of restoring white, straight, male dominance – turning back the clock on perceived losses.

His supporters famously chanted “You will not replace us” during the Charlottesville neo-Nazi march, blending anti-Black and anti-Jewish conspiracies with the general replacement fear. Even mainstream Republicans have flirted with this: one U.S. Congressman tweeted about declining white birth rates being a concern, essentially laundered Great Replacement theory.

The Strongman Fixation

The Hobbesian view of life as “nasty, brutish, and short” – a war of all against all – underpins the reactionary zero-sum worldview. Thomas Hobbes argued that without strong authority, human competition for resources and security creates constant conflict. Reactionaries often implicitly endorse this bleak view: they don’t believe in win-win solutions or cooperative progress. To them, society without the old hierarchies is a war of each identity group against each other.

The only way to have peace (and for them to be safe) is to reassert their dominance as the Leviathan keeping others in check. It’s why authoritarian “strongman” leadership so often appeals to reactionary constituencies – they want a champion who will ensure their side wins the zero-sum game. Democracy, with its compromises and shifting coalitions, is unsettling because it could hand the reins to the “Others” in some election. Far better to have a fixed hierarchy, guaranteed by force if necessary.

Misreadings of Might

Nietzsche’s Übermensch concept – the idea of a figure who creates his own values through strength of will – is sometimes hijacked in these contexts to justify trampling the weak. Indeed, many alt-right and neo-fascist thinkers lionise Nietzsche (often out of context), seeing themselves as the new masters who reject the “slave morality” of equality and compassion. 27Sean Illing, The alt-right is drunk on bad readings of Nietzsche. The Nazis were too., 17 August 2017.

For instance, some incel manifestos and alt-right blogs explicitly reference the will to power and celebrate a coming era where the “fittest” (in their view, white males) will regain supremacy by casting off the moral shackles of liberalism. This is obviously a warped interpretation of Nietzsche (who likely would have scorned their small-minded bigotries), but it shows how the zero-sum, might-makes-right creed can borrow pseudo-philosophical glamour.

Essentially, they claim it’s natural or noble for the strong to dominate – so any attempts at levelling the playing field (be it feminism or socialism or human rights law) are framed as artificial and repressive.

The Cost of Division

The danger of the zero-sum worldview is that it becomes self-fulfilling. If a society believes it has no common ground and is locked in permanent intergroup competition, then cooperation erodes and polarisation deepens. Each side arms itself (sometimes literally) for impending conflict. We’ve seen glimmers of this in militia movements and civil war talk in the U.S., in communal riots in India, in the resurgence of armed far-right groups in Germany. It’s a mentality that easily slides into eliminationism: the idea that the solution is to eliminate the other side entirely (through deportation, exclusion, imprisonment, or worse). The Rohingya genocide in Myanmar was fuelled by zero-sum rhetoric: the Buddhist nationalist narrative said any presence of Rohingya Muslims was a threat to Buddhist dominance, so the “solution” was to drive them out all together. 28Barbara Ortutay, Amnesty report finds Facebook amplified hate ahead of Rohingya massacre in Myanmar, 29 September 2022. When zero-sum thinking goes extreme, it ends in ethnic cleansing or apartheid or endless civil strife.

On a more everyday level, zero-sum framing stymies policies that could benefit everyone.

🇪🇺 For example, far-right parties in Europe often oppose welfare spending not only on fiscal grounds but because they don’t want immigrants or minorities to benefit – even if that means poor “native” citizens also get less help.

🇺🇸 In the U.S., many working-class whites turned against programs like welfare and Medicaid from the 1970s onward because conservative messaging convinced them these programs primarily helped undeserving minorities at their expense. The tragic irony is that this allowed neoliberal austerity to cut the safety net for all, harming those very working-class communities. Zero-sum thinking was used as a wedge to prevent multiracial solidarity.

🇿🇦 In South Africa, anti-immigrant sentiment distracts from systemic problems and leads people to attack fellow poor Africans instead of, say, holding corrupt officials accountable who fail to provide services.

Thus, the “divide and conquer” tactic of elites throughout history often leans on instilling zero-sum beliefs among the populace.

A Better Story: From Fear to Shared Future

In closing this section, it’s worth contrasting the zero-sum philosophy with a positive-sum or common good philosophy. The latter underpinned much of the post-WWII liberal order – the idea that expanding human rights, education, and economic opportunity creates more prosperity and stability for all. That worldview treats justice as generative: freeing the oppressed adds to society’s creative and moral wealth, rather than subtracting from someone else’s share.

But the reactionaries do not see the world that way. They hark back to older views: life as a battlefield, civilisation as a fortress to be defended, greatness as the subjugation of others. This is why their politics often glorifies past eras of conquest or strict social order. They yearn for a mythic time when their group had unchallenged supremacy – be it Victorian Britain, or 1950s America, or imperial Japan, or ancient Rome. In reality, those eras had their own profound conflicts and suffering, but in the nostalgic imagination they represent high-water marks of us winning.

Philosophically, one might say the reactionaries are stuck in a Hobbesian state of nature mindset, whereas progressives strive for a Rawlsian just society (John Rawls, by contrast, imagined designing society from behind a veil of ignorance to be fair to all). The reactionaries effectively reject the veil of ignorance: they are acutely aware of who they are (e.g., a white Christian man), and want the rules rigged accordingly. It is a grim philosophy, but it appeals strongly to those who feel their back is against the wall. If one truly believes any concession leads to doom, one will fight with ferocity and without scruple. That is what we are up against: a worldview that cannot easily be appeased with half-measures, because it interprets any compromise as weakness and fuel for further aggression.

Only by breaking out of the zero-sum trap – finding narratives of shared destiny and mutual benefit – can pluralistic societies hope to calm this existential fight. Otherwise, we risk heading toward exactly the kind of widespread conflict the reactionaries ominously predict.

Social Media Algorithms & Global Digital Radicalisation

The Algorithms of Amplification

In the 21st century, the spread of reactionary ideas and the knitting together of extremist subcultures would have been impossible at this scale without the catalysing force of social media algorithms. The digital ecosystem – Facebook, YouTube, Twitter (X), TikTok, Reddit, WhatsApp, and beyond – has proven to be a double-edged sword for democracy.

- On one hand, it amplifies marginalised voices and exposes people to diverse perspectives.

- On the other, it has functioned as a radicalisation accelerant, recommendation engines leading users down rabbit holes of hate, and a global conveyor belt for misinformation.

As media theorist Marshall McLuhan presciently noted, “the medium is the message”, and in this case, the medium (algorithm-driven social platforms) has shaped the message (reactionary radicalisation) in profound ways. The very architecture of social media – optimising for engagement, which often means outrage or fear – has turned it into a breeding ground for extremist beliefs.

Global Platforms, Local Violence

🇲🇲 One stark example is how Facebook’s algorithms contributed to the genocide in Myanmar. The Rohingya Muslim minority had faced discrimination for decades, but it was the advent of Facebook (which became effectively the internet for many Burmese) that turbocharged hate propaganda against them. An Amnesty International report found that Facebook’s recommendation algorithm “proactively amplified” anti-Rohingya content, driving people toward militant Buddhist nationalist pages and posts that incited violence. 29Amnesty International, Myanmar: The social atrocity: Meta and the right to remedy for the Rohingya, 29 September 2022. Hate speech spread like wildfire on people’s feeds – “the theme of societal decline is metonymically expressed in the wounded masculinities of the majority male,” to borrow the earlier phrasing, and in Myanmar, this took the form of fears that Muslim presence threatened Buddhist manhood and nationhood. 30Alan Greig, Masculinities and the Rise of the Far-Right: Implications for Oxfam’s Work on Gender Justice, February 2020. Despite years of warnings, Facebook did too little, too late to curb this. In 2017, these online flames translated into real-world atrocity: military-led massacres, mass rape, and the exodus of over 700,000 Rohingya to refugee camps. A U.N. investigator flatly declared Facebook had become a “useful instrument” for ethnic cleansing. 31Human Rights Council, Report of the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar, 24 August 2018. The company’s own internal studies (revealed later) showed they knew the algorithm was steering users to extreme content but feared clamping down would hurt “engagement,” and thus profits. In short, an algorithm optimised for keeping attention ended up optimising for genocide. This horrifying case lays bare the stakes of algorithmic radicalisation in fragile societies.

🇮🇳 Another case: WhatsApp-fuelled lynchings in India. In 2017–2018, rumours of child kidnappers roaming villages went viral via WhatsApp forwards (often with sensational fake videos attached). In a country with over 200 million WhatsApp users, many new to smartphones and prone to trusting messages from “friends of friends,” these rumours triggered mass panic. Within months, more than two dozen innocent people were beaten to death by mobs across India, mistaken for the fictitious kidnappers. 32Alex Hern, WhatsApp to restrict message forwarding after India mob lynchings, 20 July 2018. One chilling incident saw a tech worker visiting a rural area murdered by villagers who had seen WhatsApp messages warning “outsiders” were stealing kids. Despite efforts by authorities and WhatsApp to debunk the hoaxes (WhatsApp even changed its forwarding limits and took out newspaper ads urging users to verify information), the violence continued for some time. This is a case of algorithmic radicalisation in a slightly different sense – here it wasn’t a recommendation feed, but the virality and encryption of the platform that did the damage. WhatsApp’s design allows rumours to spread peer-to-peer rapidly, with no easy way for fact-checkers or police to intercept. It created an information cascade with no central control. The result was a classic moral panic leading to vigilantism, except now supercharged to occur in multiple places at once thanks to digital networking.

From Curiosity to Cult: The Algorithmic Funnel